| Ani Liu |  |

|||

| In the summer of 2017 I was fortunate to visit a series of factories in Shenzhen and Dongguan. Most of the factories were circuit-board factories, and they ranged in their human friendliness. Some were almost fully automated, sterile white environments with robots being tended to by one or two people in hazmat suits. In contrast were my site visits to acrid industrial floors splashed with chemicals, and filled with shirtless workers sweating over copper plates in rubber boots. I was very taken with the scale of manufacture, and the ratio in which the machines outnumbered the humans. In some senses, the machine reigned high on the priority hierarchy, with seemingly no one looking out for the human. From these experiences, I was inspired to make work about manufacturing and its impact on human labor. I was particularly interested in the worker's emotional relationship to the end product. |

||||

|

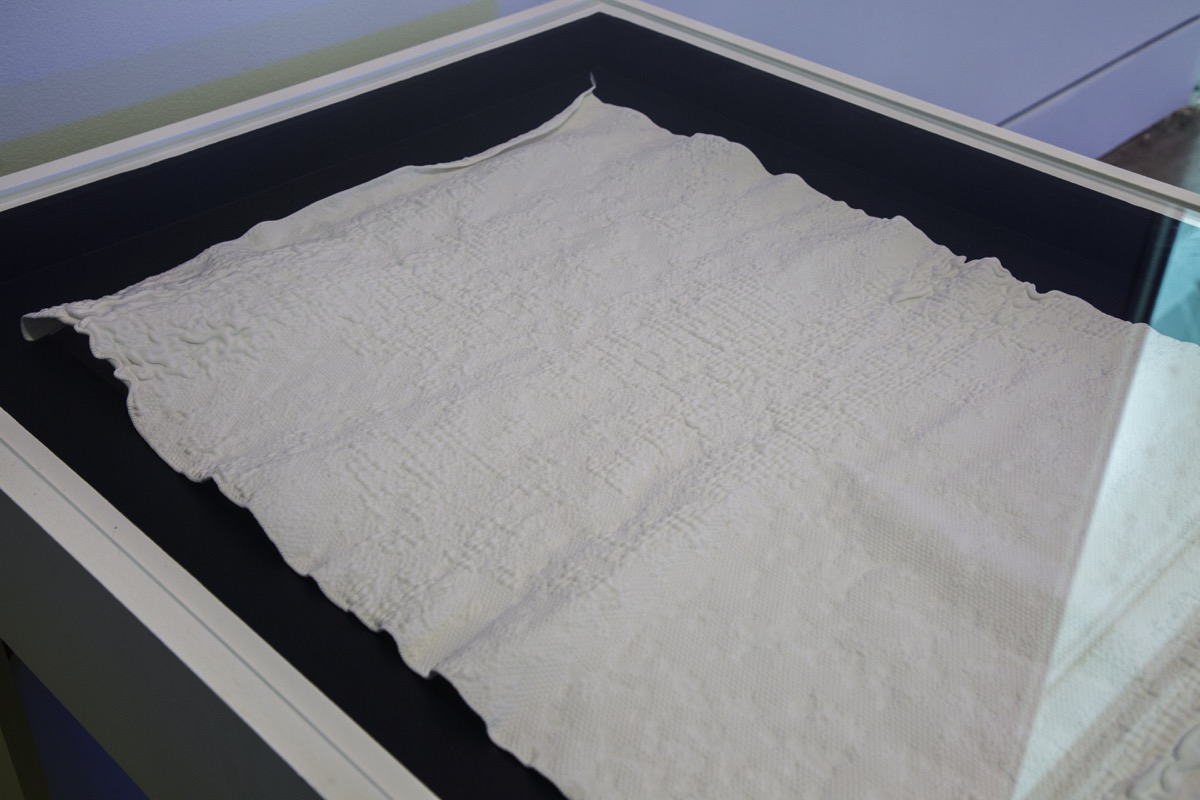

For QI 2018, I am entangling the production of textile with the emotional experience of the worker, taking the brainwave signals of a factory worker and programming the machine she uses to create a knit that reflects her cognitive states. When she is stressed, areas of the knit are tighter; where she is more relaxed, the stitch is looser. Knitting itself is a very old technology that is embedded with culture, tradition, and sentiment. I personally have a few garments knit for me by my grandmother before I was born, and I treasure them for the way each loop represents a moment her fingers moved over fibers to create something as an act of love for me. I also love seeing the imperfections—moments where her mind wandered and she slipped a stitch, or quirky lopsided edges where she seemed anxious and knit more tightly than the rest of the garment. I became very interested to see if very human and emotional moments like these could be captured by a CNC knitting machine. |

|||

| There were a lot of challenges in the making of this piece, including the many language barriers—from me not speaking Mandarin to learning a new programming language, to the pure shock of how hot and humid the environment was. I was also nervous about creating work about labor in a Chinese factory, as it could be perceived as quite political. Even though we could barely exchange full sentences to each other, there were a lot of meaningful exchanges through gestures, actions, and facial expressions. Thus, I really did get somewhat emotionally attached, and the project was meaningful to me. Of course, EEG signals are not a perfect technology by far, and I certainly could not see into anyone's thoughts. But somehow having small snapshots of their biometric signature felt special to me, like a different sort of memento. |

||||

|

The obsession with science and technology in my art practice probably reflects an undercurrent of the idealism around math and science fueled by the economic anxieties of growing up in an immigrant household. Taking back this anxiety for artistic expression, my work imbues scientific processes with personal narrative and emotional expression. Sliding back and forth between making data visceral and the unknowable quantifiable, my work operates at the tension between my rational and emotional self. | |||

| Trained as an architect, my response to volumes was initially spatial. In the design process, we often look for parameters to shape the volume—whether it be economic, social, cultural, or environmental, and to me, volumes speaks to the underlying invisible forces that shape things and their interrelationships to become the way they are. As a child, I was given a set of encyclopedias so old that most of the information was outdated by the time I read them. I discovered that the company released a new volume every year, to correct and update itself with the changes taking place. That truth is never static, that it is always adding to itself, in a contradicting, uncomfortable, and hopeful aggregate—that is what volumes evokes in me. |

||||

| prev | Ani Liu (b. 1986, New York, NY) earned a MSc from MIT Media Lab (2017), a MArch from Harvard Graduate School of Design (2014), and a BA from Dartmouth College (2008). She is the winner of the Biological Art and Design Award, Amsterdam, the Netherlands (2018). She has exhibited her work internationally, including a solo show at la Factoría Cultural in Avíles, Spain (2018), and the Boston Center for the Arts, MA (2017), and group exhibitions at Mana Contemporary, Jersey City, NJ (2018); Shenzhen Design Society, Shenzhen, China (2018, 2017); Paul Robeson Galleries, Newark, NJ (2018); Open Gallery, Boston, MA (2017); Wiesner Gallery, Cambridge, MA (2017); MFA Now Series at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA (2017); Grounded Visionaries, Harvard Graduate School of Design, Cambridge, MA (2014); SciEx Film Festival, MIT Museum, Cambridge, MA (2014); ISE Cultural Foundation, New York, NY (2009); and Barrows Rotunda, Hopkins Center, Hanover, NH (2008). She was an artist-in-residence at Triangle Arts Association (2015). She lives in Astoria, Queens and works in Long Island City, Queens. | next | ||

| prev | next | |||