| Christina Freeman |  |

|||

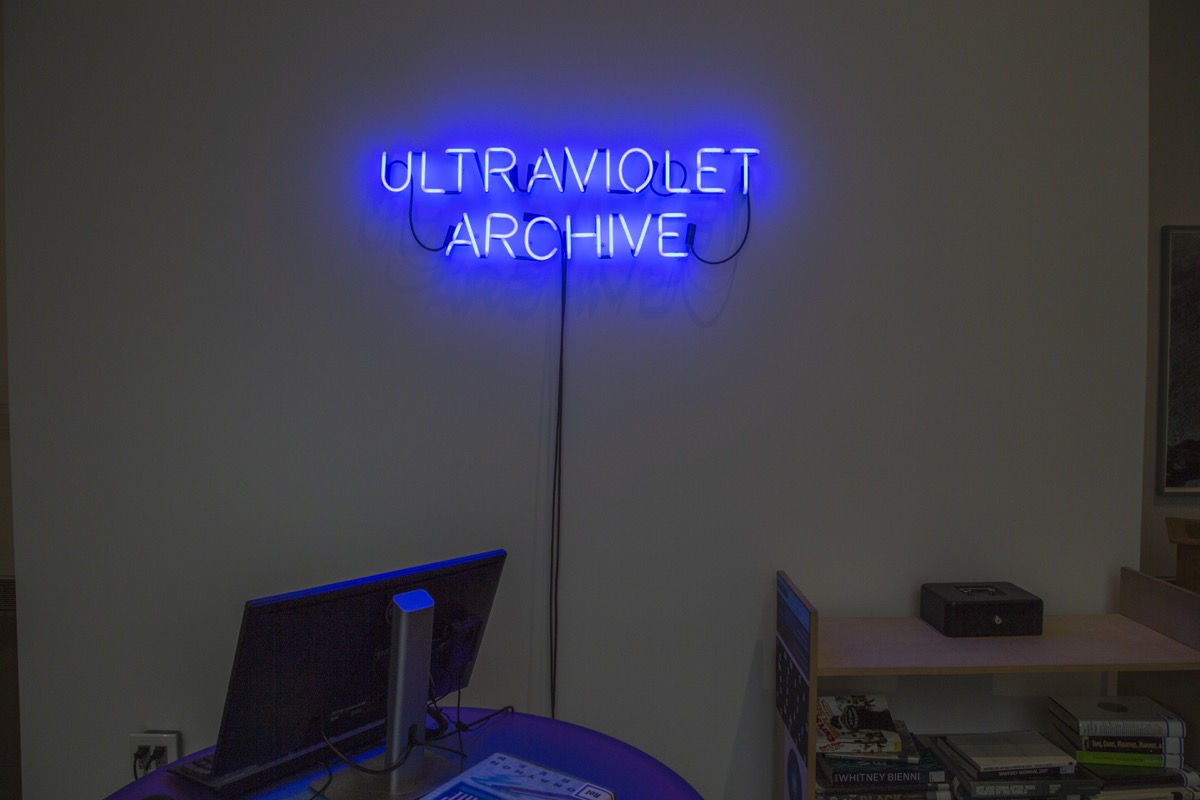

| As a nomadic project and event space, UltraViolet Archive provides visibility for and access to challenged creative works. Named after the wavelengths of light outside the visible spectrum, the material featured within this archive has faced the threat of public invisibility, due to banning, cultural amnesia, bias, self-censorship, and other challenges. By featuring visual arts, literature, films, graphic novels, music and performing arts, the installation highlights that no medium is immune to censorship. | ||||

| In a Spanish cinema course in college, I was fascinated to learn that (aside from art house films) all movies coming into Spain from abroad are dubbed rather than subtitled. This is a result of state control under the dictator Francisco Franco. Regional languages in Spain have always been deeply connected to identity. By dubbing all films in Castilian Spanish, Franco reinforced his nationalist agenda and suppressed local languages like Catalan or Basque. It is also widely documented that this policy was one method the Franco regime used to filter out foreign ideas considered subversive. Even thirty years after the end of the dictatorship, when I lived in Barcelona, dubbing was still the norm. It was what everyone was accustomed to, and many Spaniards preferred dubbing over subtitles. When the voice actor who regularly portrayed Clint Eastwood passed away, the country was in mourning, and it was upsetting for everyone to think of adjusting to a new voice. Dubbing, an aspect of state censorship, had become normalized and even beloved by the general population. I'm also inspired by the way artists work within and around various limitations. Juan Rulfo's novel Pedro Páramo exemplifies an author's creative response to an inability to openly critique the government. The main character's endless search through ghost towns for the father who abandoned him still functions as a powerful metaphor for a government abandoning its people. Gabriel García Márquez cites this classic Mexican novel as a major inspiration for his style, marking it as a precursor to magical realism. In the United States, magical realism is often divorced from its political origin. The fact that the genre developed in response to limited freedoms of speech is essential to the fully appreciate the work. |

||||

|

|

|||

| What does it mean to narrow this project to New York-related, Queens Library circulating items? | What does it mean to narrow this project to New York-related, Queens Library circulating items? | This iteration of the UltraViolet Archive is limited to circulating items in the Queens Library system that relate to the censorship history of New York. Items in the installation will continue to be available to the public at the Queens Library following the exhibition. This local approach will help make the challenges and triumphs around censorship feel present and tangible. Launching this project at the Queens Museum means that I am able to develop a partnership with the Queens Library that otherwise would not be possible. The location will also greatly increase the visibility of the project, hopefully allowing it to travel, expand and exist in various iterations going forward. |

||

| What types of conversations do you set the stage for? | Process is essential to my practice, and my projects will grow or change throughout the duration of an exhibition. I'm often more interested in conversation and ephemeral interactions than in the physical art object. The installation or performance creates a setting to facilitate this conversation. In the UltraViolet Archive, I hope to provide a complex perspective on how censorship influences creative works, by presenting a wide range of works in various media, across time periods, along with the different contexts for each challenge. I would like to show the full spectrum, from works suppressed by state censorship or bias to those challenged by individuals or special interest groups to artists censoring themselves. In conversations with friends and colleagues, I'm observing that there is no consensus about how censorship is currently defined. A large aspect of this project will include making space for the public to engage in that conversation. |

What types of conversations do you set the stage for? | ||

| prev | Christina Freeman (b. 1983, Wilmington, DE) received an MFA in Studio Art from CUNY Hunter College (2012) and a BA in Spanish and Latin American Studies from Haverford College (2005). She was the recipient of the Tuttle Fund, the Graf Travel Grant, the Pickett Fund Award, CUNY PSC Grant, and the Center for Peace and Global Citizenship award. She has exhibited her immersive and participatory projects internationally, including Flux Factory, Long Island City, NY (2016); TEM market, Volos, Greece (2013); The Red House, Sofia, Bulgaria (2012); SOMA, Mexico City (2012); and Galería Perdida Michoacán, Mexico (2012). She has organized exhibitions and events for Flux Factory (2018 and 2017); ABC No Rio in exile (2018 and 2017); Hunter East Harlem Gallery (2017); Temporary Agency (2016); The College Art Association (2015); and The Clemente Soto Velez (2011). Freeman has been an artist-in-residence at ARoS Public (2018), Flux Factory (2016-2018), Heliopolis (2014), Thomas Hunter Project Space (2013), SEDEPAC (2005) and Norris Square Neighborhood Project (2004). Christina teaches in the Fine Arts Department at Haverford College and the Department of Art and Art History at Hunter College, CUNY. She lives in Sunnyside and works in Long Island City, Queens. | next | ||

| prev | next | |||